The following videos will give you the goal of this website; which is to describe how the Earth will be the primary instrument, by way of Earthquakes and Volcanoes as the means of the Great Tribulation Period events.

The Ring of Fire (also known as the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Rim of Fire, the Girdle of Fire or the Circum-Pacific belt)[note 1] is a tectonic belt of volcanoes and earthquakes.

It is about 40,000 km (25,000 mi) long[1] and up to about 500 km (310 mi) wide,[2] and surrounds most of the Pacific Ocean.

The Ring of Fire contains between 750 and 915 active or dormant volcanoes, around two-thirds of the world total.[3][4] The exact number of volcanoes within the Ring of Fire depends on which regions are included.

About 90% of the world’s earthquakes,[5] including most of its largest,[6][7] occur within the belt.

The Ring of Fire is not a single geological structure. It was created by the subduction of different tectonic plates at convergent boundaries around the Pacific Ocean. These include: the Antarctic, Nazca and Cocos plates subducting beneath the South American plate; the Pacific and Juan de Fuca plates beneath the North American plate; the Philippine Plate beneath the Eurasian plate; and a complex boundary between the Pacific and Australian plate. The interactions at these plate boundaries have formed oceanic trenches, volcanic arcs, back-arc basins and volcanic belts.[8] The inclusion of some areas in the Ring of Fire, such as the Antarctic Peninsula and western Indonesia, is disputed.

The Ring of Fire has existed for more than 35 million years[9] but subduction has existed for much longer in some parts of the Ring;[10] many older extinct volcanoes are located within the Ring.[3] More than 350 of the Ring of Fire’s volcanoes have been active in historical times,[11][note 2] while the four largest volcanic eruptions on Earth in the Holocene epoch all occurred at volcanoes in the Ring of Fire.[13]

Most of Earth’s active volcanoes with summits above sea level are located in the Ring of Fire.[14] Many of these subaerial volcanoes are stratovolcanoes (e.g. Mount St. Helens), formed by explosive eruptions of tephra alternating with effusive eruptions of lava flows. Lavas at the Ring of Fire’s stratovolcanoes are mainly andesite and basaltic andesite but dacite, rhyolite, basalt and some other rarer types also occur.[3] Other types of volcano are also found in the Ring of Fire, such as subaerial shield volcanoes (e.g. Plosky Tolbachik), and submarine seamounts (e.g. Monowai).

History

From Ancient Greek and Roman times until the late 18th century, volcanoes were associated with fire, based on the ancient belief that volcanoes were caused by fires burning within the Earth.[15] This historical link between volcanoes and fire is preserved in the name of the Ring of Fire, despite the fact that volcanoes do not burn the Earth with fire.

The existence of a belt of volcanic activity around the Pacific Ocean was known in the early 19th century; for example, in 1825 the pioneering volcanologist G. P. Scrope described the chains of volcanoes around the Pacific Ocean’s rim in his book Considerations on Volcanos [sic].[16] Three decades later, a book about the Perry Expedition to Japan commented on the Ring of Fire volcanoes as follows: “They [the Japanese Islands] are in the line of that immense circle of volcanic development which surrounds the shores of the Pacific from Tierra del Fuego around to the Moluccas.” (Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, 1852–54.[17]) An article appeared in Scientific American in 1878 with the title “The Ring of Fire, and the Volcanic Peaks of the West Coast of the United States”, which outlined the phenomenon of volcanic activity around the boundaries of the Pacific.[18] Early explicit references to volcanoes forming a “ring of fire” around the Pacific Ocean also include Alexander P. Livingstone’s book “Complete Story of San Francisco’s Terrible Calamity of Earthquake and Fire”, published in 1906, in which he describes “… the great ring of fire which circles round the whole surface of the Pacific Ocean.”.[19]

In 1912, geologist Patrick Marshall introduced the term “Andesite Line” to mark a boundary between islands in the southwest Pacific, which differ in volcano structure and lava types. The concept was later extended to other parts of the Pacific Ocean.[20] The Andesite Line and the Ring of Fire closely match in terms of location.[21]

The development of the theory of plate tectonics since the early 1960s has provided the current understanding and explanation of the global distribution of volcanoes and earthquakes, including those in the Ring of Fire.[22][23]

Geographic boundaries

There is consensus among geologists about most of the regions which are included in the Ring of Fire. There are, however, a few regions on which there is no universal agreement. (See: § Distribution of volcanoes). Indonesia lies at the intersection of the Ring of Fire and the Alpide belt (which is the Earth’s other very long subduction-related volcanic and earthquake zone, also known as the Mediterranean–Indonesian volcanic belt, running east–west through southern Asia and southern Europe).[24][25][26] Some geologists include all of Indonesia in the Ring of Fire;[27] many geologists exclude Indonesia’s western islands (which they include in the Alpide belt).[28][25][29][30][31]

Some geologists include the Antarctic Peninsula and the South Shetland Islands in the Ring of Fire,[29][30] other geologists exclude these areas.[27] The rest of Antarctica is excluded because the volcanism there is not related to subduction.[32][31]

The Ring of Fire does not extend across the southern Pacific Ocean from New Zealand to the Antarctic Peninsula or from New Zealand to the southern tip of South America[33] because the submarine plate boundaries in this part of the Pacific Ocean (the Pacific–Antarctic Ridge, the East Pacific Rise and the Chile Ridge) are divergent instead of convergent. Although some volcanism occurs in this region, it is not related to subduction.

Some geologists include the Izu Islands, the Bonin Islands, and the Mariana Islands,[27][34][35] other geologists exclude them.[33]

Land areas

- Antarctica

- Andes

- Central America Volcanic Arc

- North American Cordillera

- Kamchatka Peninsula

- Kuril Islands

- Japan

- Ryukyu Islands

- Taiwan

- Philippine Mobile Belt

- Izu–Bonin–Mariana Arc

- Tanimbar and Kai Islands

- Bismarck Archipelago

- Vanuatu

- Bougainville Island

- Solomon Islands

- Fiji

- Tonga Islands

- Kermadec Islands

- Taupō Volcanic Zone

Volcanoes in the central parts of the Pacific Basin, for example the Hawaiian Islands, are very far from subduction zones[36] and they are not part of the Ring of Fire.[37]

Tectonic plate configurations

The Ring of Fire has existed for more than 35 million years.[9] In some parts of the Ring of Fire, subduction has been occurring for much longer.[38]

The current configuration of the Pacific Ring of Fire has been created by the development of the present-day subduction zones, initially (by about 115 million years ago) in South America, North America and Asia. As plate configurations gradually changed, the current subduction zones of Indonesia and New Guinea were created (about 70 million years ago), followed finally by the New Zealand subduction zone (about 35 million years ago).[39][9]

Past plate configurations

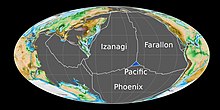

Along the coast of east Asia, during the Late Triassic about 210 million years ago, subduction of the Izanagi plate (the Paleo-Pacific plate) was occurring,[39] and this continued in the Jurassic, producing volcanic belts, for example, in what is now eastern China.[40]

The Pacific plate came into existence in the Early Jurassic about 190 million years ago,[41] far from the margins of the then Paleo-Pacific Ocean. Until the Pacific plate grew large enough to reach the margins of the ocean basin, other older plates were subducted ahead of it at the ocean basin margins. For example, subduction has been occurring at the coast of South America since the Jurassic Period more than 145 million years ago, and remnants of Jurassic and Cretaceous volcanic arcs are preserved there.[42]

At about 120 to 115 million years ago, the Farallon plate was subducting under South America, North America and north-east Asia while the Izanagi plate was subducting under east Asia. By 85 to 70 million years ago, the Izanagi plate had moved north-eastwards and was subducting under east Asia and North America, while the Farallon plate was subducting under South America and the Pacific plate was subducting under east Asia. About 70 to 65 million years ago, the Farallon plate was subducting under South America, the Kula plate was subducting under North America and north-east Asia, and the Pacific plate was subducting under east Asia and Papua New Guinea. About 35 million years ago, the Kula and Farallon plates had been subducted and the Pacific plate was subducting around its rim in a configuration closely resembling the outline of the present-day Ring of Fire.[39][43][44]

Present-day plate configuration

The eastern parts of the Ring of Fire result from the collision of a few relatively large plates. The western parts of the Ring are more complex, with a number of large and small tectonic plates in collision.[45]

In South America, the Ring of Fire is the result of the Antarctic plate, the Nazca plate and the Cocos plate being subducted beneath the South American plate. In Central America, the Cocos plate is being subducted beneath the Caribbean plate. A portion of the Pacific plate and the small Juan de Fuca plate are being subducted beneath the North American plate. Along the northern portion, the northwestward-moving Pacific plate is being subducted beneath the Aleutian Islands arc. Farther west, the Pacific plate is being subducted at the Kamchatka Peninsula and Kuril arcs. Farther south, at Japan, Taiwan and the Philippines, the Philippine Plate is being subducted beneath the Eurasian plate. The southwest section of the Ring of Fire is more complex, with a number of smaller tectonic plates in collision with the Pacific plate at the Mariana Islands, the Philippines, eastern Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Tonga, and New Zealand; this part of the Ring excludes Australia, because that landmass lies in the center of its tectonic plate far from subduction zones.[45]

Subduction zones and oceanic trenches

If a tectonic plate’s oceanic lithosphere is subducted beneath oceanic lithosphere of another plate, a volcanic island arc is created at the subduction zone. An example in the Ring of Fire is the Mariana Arc in the western Pacific Ocean. If, however, oceanic lithosphere is subducted under continental lithosphere, then a volcanic continental arc forms; a Ring of Fire example is the coast of Chile.[2]

The steepness of the descending plate at a subduction zone depends on the age of the oceanic lithosphere that is being subducted. The older the oceanic lithosphere being subducted, the steeper the angle of descent of the subducted slab. As the Pacific’s mid-ocean ridges, which are the source of its oceanic lithosphere, are not actually in the middle of the ocean but located much closer to South America than to Asia, the oceanic lithosphere consumed at the South American subduction zones is younger and therefore subduction occurs at the South American coast at a relatively shallow angle. Older oceanic lithosphere is subducted in the western Pacific, with steeper angles of slab descent. This variation affects, for example, the location of volcanoes relative to the ocean trench, lava composition, type and severity of earthquakes, sediment accretion, and the amount of compression or tension. A spectrum of subduction zones exists between the Chilean and Mariana end members.[46][2]

Oceanic trenches

Oceanic trenches are the topographic expression of subduction zones on the floor of the oceans. Oceanic trenches associated with the Ring of Fire’s subduction zones are:

- Peru–Chile Trench

- Middle America Trench

- Aleutian Trench

- Kuril–Kamchatka Trench

- Japan Trench

- Ryukyu Trench

- Izu–Bonin Trench

- Mariana Trench

- Yap Trench

- Philippine Trench

- Sunda Trench

- Tonga Trench

- Kermadec Trench

- Hikurangi Trough

Gaps

Subduction zones around the Pacific Ocean do not form a complete ring. Where subduction zones are absent, there are corresponding gaps in subduction-related volcanic belts in the Ring of Fire. In some gaps there is no volcanic activity; in other gaps, volcanic activity does occur but it is caused by processes not related to subduction.

There are gaps in the Ring of Fire at some parts of the Pacific coast of the Americas. In some places, the gaps are thought to be caused by flat slab subduction; examples are the three gaps between the four sections of the Andean Volcanic Belt in South America.[47] In North America, there is a gap in subduction-related volcanic activity in northern Mexico and southern California, due partly to a divergent boundary in the Gulf of California and due partly to the San Andreas Fault (a non-volcanic transform boundary). Another North American gap in subduction-related volcanic activity occurs in northern British Columbia, Yukon and south-east Alaska, where volcanism is caused by intraplate continental rifting.[22]

Volcanic eruptions

The four largest volcanic eruptions on Earth in the Holocene Epoch (the last 11,700 years) occurred at volcanoes in the Ring of Fire. They are the eruptions at Fisher Caldera (Alaska, 8700 BC), Kurile Lake (Kamchatka, 6450 BC), Kikai Caldera (Japan, 5480 BC) and Mount Mazama (Oregon, 5677 BC).[13] More broadly, twenty[note 3] of the twenty-five largest volcanic eruptions on Earth in this time interval occurred at Ring of Fire volcanoes.[13]

Earthquakes

About 90%[5] of the world’s earthquakes and most of the world’s largest earthquakes occur along the Ring of Fire.[note 4] The next most seismically active region (5–6% of earthquakes and some of the world’s largest earthquakes) is the Alpide belt, which extends from central Indonesia to the northern Atlantic Ocean via the Himalayas and southern Europe.[6][7]

From 1900 to the end of 2020, most earthquakes of magnitude Mw ≥ 8.0 occurred in the Ring of Fire.[54][note 5] They are presumed to have been megathrust earthquakes at subduction zones,[54] including four of the most powerful earthquakes on Earth since modern seismological measuring equipment and magnitude measurement scales were introduced in the 1930s:

- 1960 Valdivia earthquake, Chile (magnitude Mw 9.4–9.6)

- 1964 Alaska earthquake, Alaska, United States (magnitude Mw 9.2)

- 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, Japan (magnitude Mw 9.0–9.1)

- 1952 Severo-Kurilsk earthquake, Kamchatka, Russia (magnitude Mw 9.0)

Antarctica

Some geologists include the volcanoes of the South Shetland Islands, off the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, as part of the Ring of Fire. These volcanoes, e.g. Deception Island, are due to rifting in the Bransfield back-arc basin close to the South Shetland subduction zone.[56] The Antarctic Peninsula (Graham Land) is also sometimes included in the Ring.[57] Volcanoes south of the Antarctic Circle (e.g. the volcanoes of Victoria Land including Mount Erebus, and the volcanoes of Mary Byrd Land) are not related to subduction; therefore, they are not part of the Ring of Fire.[31]

The Balleny Islands, located between Antarctica and New Zealand, are volcanic but their volcanism is not related to subduction;[58] therefore, they are not part of the Ring of Fire.

South America

The world’s highest active volcano is Ojos del Salado (6,893 m or 22,615 ft), which is in the Andes Mountains section of the Ring of Fire. It forms part of the border between Argentina and Chile and it last erupted in AD 750.[59] Another Ring of Fire Andean volcano on the Argentina-Chile border is Llullaillaco (6,739 m or 22,110 ft), which is the world’s highest historically active volcano, last erupting in 1877.[60]

Chile

Chile has experienced numerous volcanic eruptions from about 90 volcanoes during the Holocene Epoch.[3]

Villarrica is one of Chile’s most active volcanoes, rising above the lake and town of the same name. It is the westernmost of three large stratovolcanoes that trend perpendicular to the Andes along the Gastre Fault. Villarrica, along with Quetrupillán and the Chilean part of Lanín, are protected within Villarrica National Park.

Villarrica, with its lava of basaltic-andesitic composition, is one of only five volcanoes worldwide known to have an active lava lake within its crater. The volcano usually generates strombolian eruptions, with ejection of incandescent pyroclasts and lava flows. Melting of snow and glacier ice, as well as rainfall, often causes lahars, such as during the eruptions of 1964 and 1971.[61]

A two-kilometre-wide (1+1⁄4 mi) postglacial caldera is located at the base of the presently active dominantly basaltic-to-andesitic cone at the northwest margin of the Pleistocene caldera. About 25 scoria cones dot Villarica’s flanks. Plinian eruptions and pyroclastic flows have been produced during the Holocene from this dominantly basaltic volcano, but historical eruptions have consisted of largely mild-to-moderate explosive activity with occasional lava effusion. Lahars from the glacier-covered volcanoes have damaged towns on its flanks.

The Llaima Volcano is one of the largest and most active volcanoes in Chile. It is situated 82 km (51 mi) northeast of Temuco and 663 km (412 mi) southeast of Santiago, within the borders of Conguillío National Park. Llaima’s activity has been documented since the 17th century, and consists of several separate episodes of moderate explosive eruptions with occasional lava flows.

Lascar is a stratovolcano and the most active volcano of the northern Chilean Andes. The largest eruption of Lascar took place about 26,500 years ago, and following the eruption of the Tumbres scoria flow about 9,000 years ago, activity shifted back to the eastern edifice, where three overlapping craters were formed. Frequent small-to-moderate explosive eruptions have been recorded from Lascar in historical time since the mid-19th century, along with periodic larger eruptions that produced ash and tephra fall up to hundreds of kilometers away from the volcano. The largest eruption of Lascar in recent history took place in 1993, producing pyroclastic flows as far as 8.5 km (5 mi) northwest of the summit and ash fall in Buenos Aires, Argentina, more than 1,600 km (1,000 mi) to the southeast.

Chiliques is a stratovolcano located in the Antofagasta Region of Chile, immediately north of Cerro Miscanti. Laguna Lejía lies to the north of the volcano and has been dormant for at least 10,000 years, but is now showing signs of life. A January 6, 2002, nighttime thermal infrared image from ASTER revealed a hot spot in the summit crater, as well as several others along the upper flanks of the volcano’s edifice, indicating new volcanic activity. Examination of an earlier nighttime thermal infrared image from May 24, 2000, showed no such hot spots.[62]

Calbuco is a stratovolcano in southern Chile, located southeast of Llanquihue Lake and northwest of Chapo Lake, in Los Lagos Region. The volcano and the surrounding area are protected within Llanquihue National Reserve. It is a very explosive andesite volcano that underwent edifice collapse in the late Pleistocene, producing a volcanic debris avalanche that reached the lake. At least nine eruptions occurred since 1837, with the latest one in 1972. One of the largest historical eruptions in southern Chile took place there in 1893–1894. Violent eruptions ejected 30 cm (12 in) bombs to distances of 8 km (5.0 mi) from the crater, accompanied by voluminous hot lahars. Strong explosions occurred in April 1917, and a lava dome formed in the crater accompanied by hot lahars. Another short explosive eruption in January 1929 also included an apparent pyroclastic flow and a lava flow. The last major eruption of Calbuco, in 1961, sent ash columns 12–15 km (7.5–9.3 mi) high and produced plumes that dispersed mainly to the southeast and two lava flows were also emitted. A minor, four-hour eruption happened on August 26, 1972. Strong fumarolic emission from the main crater was observed on August 12, 1996.

Lonquimay is a stratovolocano of late-Pleistocene to dominantly Holocene age, with the shape of a truncated cone. The cone is largely andesitic, though basaltic and dacitic rocks are present. It is located in La Araucanía Region of Chile, immediately southeast of Tolhuaca volcano. Sierra Nevada and Llaima are their neighbors to the south. The snow-capped volcano lies within the protected area Malalcahuello-Nalcas. The volcano last erupted in 1988, ending in 1990. The VEI was 3. The eruption was from a flank vent and involved lava flows and explosive eruptions. Some fatalities occurred.[63]

The volcanoes in Chile are monitored by the National Geology and Mining Service (SERNAGEOMIN)[64][65]

Earthquake activity in Chile is related to subduction of the Nazca plate to the east. Chile notably holds the record for the largest earthquake ever recorded, the 1960 Valdivia earthquake. More recently, a magnitude-8.8 earthquake struck central Chile on February 27, 2010, the Puyehue-Cordón Caulle volcano erupted in 2011, and a M8.2 earthquake struck northern Chile on April 1, 2014. The main shock was preceded by a number of moderate to large shocks and was followed by a large number of moderate to very large aftershocks, including a magnitude-7.6 event on April 2.[66]

Argentina

Bolivia

Bolivia hosts active and extinct volcanoes across its territory. The active volcanoes are located in western Bolivia where they make up the Cordillera Occidental, the western limit of the Altiplano plateau. Some of the active volcanoes are international mountains shared with Chile. All Cenozoic volcanoes of Bolivia are part of the Central Volcanic Zone (CVZ) of the Andean Volcanic Belt that results due to processes involved in the subduction of the Nazca plate under the South American plate. The Central Volcanic Zone is a major late Cenozoic volcanic province.[67]

Peru

Sabancaya is an active 5,976-metre (19,606 ft) stratovolcano in the Andes of southern Peru, about 100 km (60 mi) northwest of Arequipa. It is the most active volcano in Peru, with an ongoing eruption that started in 2016.

Ubinas is another active volcano of 5,672-metre (18,609 ft) in southern Peru; its most recent eruption occurred in 2019.[68]

Volcanoes in Peru are monitored by the Peruvian Geophysical Institute.[69]

Ecuador

Cotopaxi is a stratovolcano in the Andes, located about 50 km (30 mi) south of Quito, Ecuador, South America.[70] It is the second-highest summit in the country, reaching a height of 5,897 m (19,347 ft). Since 1738, Cotopaxi has erupted more than 50 times, resulting in the creation of numerous valleys formed by mudflows around the volcano.

In October 1999, Pichincha Volcano erupted in Quito and covered the city with several inches of ash. Prior to that, the last major eruptions were in 1553[71] and in 1660, when about 30 cm of ash fell on the city.[72]

At 5,286 m (17,343 ft), Sangay Volcano is an active stratovolcano in central Ecuador, one of the highest active volcanoes in the world and is one of Ecuador’s most active volcanoes. It exhibits mostly strombolian activity; An eruption, which started in 1934, ended in 2011.[73] More recent eruptions have occurred. Geologically, Sangay marks the southern bound of the Northern Volcanic Zone, and its position straddling two major pieces of crust accounts for its high level of activity. Sangay’s roughly 500,000-year history is one of instability; two previous versions of the mountain were destroyed in massive flank collapses, evidence of which still litters its surroundings today. Sangay is one of two active volcanoes located within the namesake Sangay National Park, the other being Tungurahua to the north. As such, it has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1983.

Reventador is an active stratovolcano that lies in the eastern Andes of Ecuador. Since 1541, it has erupted over 25 times, with its most recent eruption starting in 2008 and, as of 2020, still ongoing,[74] but the largest historical eruption occurred in 2002. During that eruption, the plume from the volcano reached a height of 17 km (10+1⁄2 mi), and pyroclastic flows reached 7 km (4.3 mi) from the cone. On March 30, 2007, the volcano erupted ash again, which reached a height of about 3 km (2 mi).

In Ecuador, EPN monitors volcanic activity.

Colombia

North America

Central America

Panama

Costa Rica

Poás Volcano is an active 2,708-metre (8,885 ft) stratovolcano located in central Costa Rica; it has erupted 39 times since 1828.

The Volcanological and Seismological Observatory of Costa Rica (OVSICORI, Observatorio Vulcanológico y Sismológico de Costa Rica) at the National University of Costa Rica[75] has a dedicated team in charge of researching and monitoring the volcanoes, earthquakes, and other tectonic processes in the Central America Volcanic Arc.

Nicaragua

Honduras

El Salvador

Guatemala

In 1902, the Santa Maria Volcano erupted violently in Guatemala, with the largest explosions occurring over two days, ejecting an estimated 5.5 km3 (1+3⁄8 cu mi) of magma. The eruption was one of the largest of the 20th century, only slightly less in magnitude to that of Mount Pinatubo in 1991. The eruption had a volcanic explosivity index of 6. Today, Santiaguito is one of the world’s most active volcanoes.[citation needed]

North American Cordillera

Mexico

Volcanoes of Mexico related to subduction of the Cocos and Rivera plates occur in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, which extends 900 km (560 mi) from west to east across central-southern Mexico. Popocatépetl, lying in the eastern half of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, is the second-highest peak in Mexico after the Pico de Orizaba. It is one of the most active volcanoes in Mexico, having had more than 20 major eruptions since the arrival of the Spanish in 1519. The 1982 eruption of El Chichón, which killed about 2,000 people who lived near the volcano, created a 1-km-wide caldera that filled with an acidic crater lake. Before 1982, this relatively unknown volcano was heavily forested and of no greater height than adjacent nonvolcanic peaks.[76]

United States

The Cascade Volcanic Arc lies in the western United States. This arc includes nearly 20 major volcanoes, among a total of over 4,000 separate volcanic vents including numerous stratovolcanoes, shield volcanoes, lava domes, and cinder cones, along with a few isolated examples of rarer volcanic forms such as tuyas. Volcanism in the arc began about 37 million years ago, but most of the present-day Cascade volcanoes are less than 2 million years old, and the highest peaks are less than 100,000 years old. The arc is formed by the subduction of the Gorda and Juan de Fuca plates at the Cascadia subduction zone. This is a 1,090-kilometre-long (680 mi) fault, running 80 km (50 mi) off the coast of the Pacific Northwest from northern California to Vancouver Island, British Columbia. The plates move at a relative rate of over 10 mm (0.4 in) per year at an oblique angle to the subduction zone.

Because of the very large fault area, the Cascadia subduction zone can produce very large earthquakes, magnitude 9.0 or greater, if rupture occurred over its whole area. When the “locked” zone stores energy for an earthquake, the “transition” zone, although somewhat plastic, can rupture. Thermal and deformation studies indicate that the locked zone is fully locked for 60 km (37 mi) down-dip from the deformation front. Further down-dip, a transition from fully locked to aseismic sliding occurs.

Unlike most subduction zones worldwide, no oceanic trench is present along the continental margin in Cascadia. Instead, terranes and the accretionary wedge have been lifted up to form a series of coast ranges and exotic mountains. A high rate of sedimentation from the outflow of the three major rivers (Fraser River, Columbia River, and Klamath River) which cross the Cascade Range contributes to further obscuring the presence of a trench. However, in common with most other subduction zones, the outer margin is slowly being compressed, similar to a giant spring. When the stored energy is suddenly released by slippage across the fault at irregular intervals, the Cascadia subduction zone can create very large earthquakes such as the magnitude-9 Cascadia earthquake of 1700. Geological evidence indicates that great earthquakes may have occurred at least seven times in the last 3,500 years, suggesting a return time of 400 to 600 years. Also, evidence of accompanying tsunamis with every earthquake is seen, as the prime reason these earthquakes are known is through “scars” the tsunamis left on the coast, and through Japanese records (tsunami waves can travel across the Pacific).

The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens was the most significant to occur in the contiguous 48 U.S. states in recorded history (VEI = 5, 1.3 km3 (0.3 cu mi) of material erupted), exceeding the destructive power and volume of material released by the 1915 eruption of California’s Lassen Peak. The eruption was preceded by a two-month series of earthquakes and steam-venting episodes caused by an injection of magma at shallow depth below the mountain that created a huge bulge and a fracture system on Mount St. Helens‘ north slope. An earthquake at 8:32 am on May 18, 1980, caused the entire weakened north face to slide away, suddenly exposing the partly molten, gas-rich rock in the volcano to lower pressure. The rock responded by exploding into a very hot mix of pulverized lava and older rock that sped toward Spirit Lake so fast that it quickly passed the avalanching north face.

Alaska is known for its seismic and volcanic activity, holding the record for the second-largest earthquake in the world, the Good Friday earthquake, and having more than 50 volcanoes which have erupted since about 1760.[77] Volcanoes are found not only in the mainland, but also in the Aleutian Islands.

The United States Geological Survey and the National Earthquake Information Center monitor volcanoes and earthquakes in the United States.

Canada

British Columbia and Yukon are home to a region of volcanoes and volcanic activity in the Pacific Ring of Fire. More than 20 volcanoes have erupted in the western Canada during the Holocene Epoch but only 6 are directly related to subduction: Bridge River Cones, Mount Cayley, Mount Garibaldi, Garibaldi Lake, Silverthrone Caldera, and Mount Meager massif.[3] Several mountains in populated areas of British Columbia are dormant volcanoes. Most of these were active during the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs. Although none of Canada’s volcanoes are currently erupting, several volcanoes, volcanic fields, and volcanic centers are considered potentially active.[78] There are hot springs at some volcanoes. Since 1975, seismic activity appears to have been associated with some volcanoes in British Columbia including the six subduction-related volcanoes as well as intraplate volcanoes such as Wells Gray-Clearwater volcanic field.[78] The volcanoes are grouped into five volcanic belts with different tectonic settings.

The Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province is an area of numerous volcanoes, which are caused by continental rifting not subduction; therefore geologists often regard it as a gap in the Pacific Ring of Fire between the Cascade Volcanic Arc further south and Alaska’s Aleutian Arc further north.[79]

The Garibaldi Volcanic Belt in southwestern British Columbia is the northern extension of the Cascade Volcanic Arc in the United States (which includes Mount Baker and Mount St. Helens) and contains the most explosive young volcanoes in Canada.[80] It formed as a result of subduction of the Juan de Fuca plate (a remnant of the much larger Farallon plate) under the North American plate along the Cascadia subduction zone.[80] The Garibaldi Volcanic Belt includes the Bridge River Cones, Mount Cayley, Mount Fee, Mount Garibaldi, Mount Price, Mount Meager massif, the Squamish Volcanic Field, and more smaller volcanoes. The eruption styles in the belt range from effusive to explosive, with compositions from basalt to rhyolite. Morphologically, centers include calderas, cinder cones, stratovolcanoes and small isolated lava masses. Due to repeated continental and alpine glaciations, many of the volcanic deposits in the belt reflect complex interactions between magma composition, topography, and changing ice configurations. The most recent major catastrophic eruption in the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt was an explosive eruption of the Mount Meager massif about 2,350 years ago. It was similar to the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens,[80] sending an ash column about 20 km into the stratosphere.[81]

The Chilcotin Group is a north–south range of volcanoes in southern British Columbia running parallel to the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt. The majority of the eruptions in this belt happened either 6–10 million years ago (Miocene) or 2–3 million years ago (Pliocene), although with some slightly more recent eruptions (in the Pleistocene).[82] It is thought to have formed as a result of back-arc extension behind the Cascadia subduction zone.[82] Volcanoes in this belt include Mount Noel, the Clisbako Caldera Complex, Lightning Peak, Black Dome Mountain, and many lava flows.

Eruptions of basaltic to rhyolitic volcanoes and hypabyssal rocks of the Alert Bay Volcanic Belt in northern Vancouver Island are probably linked with the subducted margin flanked by the Explorer and Juan de Fuca plates at the Cascadia subduction zone. It appears to have been active during the Pliocene and Pleistocene. However, no Holocene eruptions are known, and volcanic activity in the belt has likely ceased.

The active Queen Charlotte Fault on the west coast of the Haida Gwaii, British Columbia, has generated three large earthquakes during the 20th century: a magnitude 7 event in 1929; a magnitude 8.1 in 1949 (Canada’s largest recorded earthquake); and a magnitude 7.4 in 1970.[83]

The Public Safety Geo-science Program at the Natural Resources Canada undertakes research to support risk reduction from the effects of space weather, earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanoes, and landslides.[84]

Asia

Russia

The Kamchatka Peninsula in the Russian Far East is one of the most active volcanic areas in the world, with 20 historically active volcanoes.[85] It lies between the Pacific Ocean to the east and the Okhotsk Sea to the west. Immediately offshore along the Pacific coast of the peninsula runs the 10,500-metre-deep (34,400 ft) Kuril–Kamchatka Trench, where subduction of the Pacific plate fuels the volcanism. Several types of volcanic activity are present, including stratovolcanoes, shield volcanoes, Hawaiian-style fissure eruptions and geysers.

Active, dormant and extinct volcanoes of Kamchatka are in two major volcanic belts. The most recent activity takes place in the eastern belt, starting in the north at the Shiveluch volcanic complex, which lies at the junction of the Aleutian and Kamchatka volcanic arcs. Just to the south is the Klyuchi volcanic group, comprising the twin volcanic cones of Kliuchevskoi and Kamen, the volcanic complexes of Tolbachik and Ushkovsky, and a number of other large stratovolcanoes. Ichinsky, the only active volcano in the central belt, is located farther to the west. Farther south, the eastern belt of stratovolcanoes continues to the southern tip of Kamchatka, continuing onto the Kuril Islands, with their 32 historically active volcanoes.[85][86]

Japan

About 10% of the world’s active volcanoes are found in Japan, which lies in a zone of extreme crustal instability. They are formed by subduction of the Pacific plate and the Philippine Sea plate. As many as 1,500 earthquakes are recorded yearly, and magnitudes of 4 to 6 are not uncommon. Minor tremors occur almost daily in one part of the country or another, causing some slight shaking of buildings. Major earthquakes occur infrequently; the most famous in the 20th century were: the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, in which 130,000 people died; and the Great Hanshin earthquake of January 17, 1995, in which 6,434 people died. On March 11, 2011 a magnitude 9.0 earthquake hit Japan, the country’s biggest ever and the fifth largest on record, according to US Geological Survey data.[87] Undersea earthquakes also expose the Japanese coastline to danger from tsunamis.

Mount Bandai, one of Japan’s most noted volcanoes, rises above the north shore of Lake Inawashiro. Mount Bandai is formed of several overlapping stratovolcanoes, the largest of which is O-Bandai, constructed within a horseshoe-shaped caldera that formed about 40,000 years ago when an earlier volcano collapsed, forming the Okinajima debris avalanche, which traveled to the southwest and was accompanied by a plinian eruption. Four major phreatic eruptions have occurred during the past 5,000 years, two of them in historical time, in 806 and 1888. Seen from the south, Bandai presents a conical profile, but much of the north side of the volcano is missing as a result of the collapse of Ko-Bandai volcano during the 1888 eruption, in which a debris avalanche buried several villages and formed several large lakes. In July 1888, the north flank of Mount Bandai collapsed during an eruption quite similar to the May 18, 1980, eruption of Mount St. Helens. After a week of seismic activity, a large earthquake on July 15, 1888, was followed by a tremendous noise and a large explosion. Eyewitnesses heard about 15 to 20 additional explosions and observed that the last one was projected almost horizontally to the north.

Mount Fuji is Japan’s highest and most noted volcano, featuring heavily in Japanese culture and serving as one of the country’s most popular landmarks. The modern postglacial stratovolcano is constructed above a group of overlapping volcanoes, remnants of which form irregularities on Fuji’s profile. Growth of the younger Mount Fuji began with a period of voluminous lava flows from 11,000 to 8,000 years ago, accounting for four-fifths of the volume of the younger Mount Fuji. Minor explosive eruptions dominated activity from 8,000 to 4,500 years ago, with another period of major lava flows occurring from 4,500 to 3,000 years ago. Subsequently, intermittent major explosive eruptions occurred, with subordinate lava flows and small pyroclastic flows. Summit eruptions dominated from 3,000 to 2,000 years ago, after which flank vents were active. The extensive basaltic lava flows from the summit and some of the more than 100 flank cones and vents blocked drainage against the Tertiary Misaka Mountains on the north side of the volcano, forming the Fuji Five Lakes. The last eruption of this dominantly basaltic volcano in 1707 ejected andesitic pumice and formed a large new crater on the east flank. Some minor volcanic activity may occur in the next few years.

Taiwan

Philippines

The 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo is the world’s second-largest eruption of the 20th century. Successful predictions of the onset of the climactic eruption led to the evacuation of tens of thousands of people from the surrounding areas, saving many lives, but as the surrounding areas were severely damaged by pyroclastic flows, ash deposits, and later, lahars caused by rainwater remobilising earlier volcanic deposits, thousands of houses were destroyed.

Mayon Volcano is the Philippines’ most active volcano. It has steep upper slopes that average 35–40° and is capped by a small summit crater. The historical eruptions of this basaltic-andesitic volcano date back to 1616 and range from Strombolian to basaltic Plinian eruptions. Eruptions occur predominately from the central conduit and have also produced lava flows that travel far down the flanks. Pyroclastic flows and mudflows have commonly swept down many of the roughly 40 ravines that radiate from the summit and have often devastated populated lowland areas.

Taal Volcano has had 33 recorded eruptions since 1572. A devastating eruption occurred in 1911, which claimed more than a thousand lives. The deposits of that eruption consist of a yellowish, fairly decomposed (nonjuvenile) tephra with a high sulfur content. The most recent period of activity lasted from 1965 to 1977, and was characterized by the interaction of magma with the lake water, which produced violent phreatic and phreatomagmatic eruptions. The volcano was dormant from 1977 then showed signs of unrest since 1991 with strong seismic activity and ground-fracturing events, as well as the formation of small mud geysers on parts of the island. An eruption occurred in January 2020.

Kanlaon Volcano, the most active volcano in the central Philippines, has erupted 25 times since 1866. Eruptions are typically phreatic explosions of small-to-moderate size that produce minor ash falls near the volcano. On August 10, 1996, Kanlaon erupted without warning, killing 3 persons who were among 24 mountain climbers trapped near the summit. On June 3, 2024, Mt. Kanlaon erupted, displacing more than 1,000 people.

Indonesia

Indonesia is located where the Ring of Fire around the Pacific Ocean meets the Alpide belt (which runs from Southeast Asia to Southwest Europe).

The eastern islands of Indonesia (Sulawesi, the Lesser Sunda Islands (excluding Bali, Lombok, Sumbawa and Sangeang), Halmahera, the Banda Islands and the Sangihe Islands) are geologically associated with subduction of the Pacific plate or its related minor plates and, therefore, the eastern islands are often regarded as part of the Ring of Fire.

The western islands of Indonesia (the Sunda Arc of Sumatra, Krakatoa, Java, Bali, Lombok, Sumbawa and Sangeang) are located north of a subduction zone in the Indian Ocean. Although news media, popular science publications and some geologists include the western islands (and their notable volcanoes such as Krakatoa, Merapi, Tambora and Toba) in the Ring of Fire, geologists often exclude the western islands from the Ring; instead the western islands are often included in the Alpide belt.[88]

Islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean

Papua New Guinea

Solomon Islands

Vanuatu

Fiji

Samoa

Tonga

New Zealand

New Zealand contains the world’s strongest concentration of youthful rhyolitic volcanoes, and voluminous sheets of tuff blanket much of the North Island. The earliest historically dated eruption was at Whakaari/White Island in 1826,[89] followed in 1886 by the country’s largest historical eruption at Mount Tarawera. Much of the region north of New Zealand’s North Island is made up of seamounts and small islands, including 16 submarine volcanoes. In the last 1.6 million years, most of New Zealand’s volcanism is from the Taupō Volcanic Zone.[90]

Mount Ruapehu, at the southern end of the Taupō Volcanic Zone, is one of the most active volcanoes in New Zealand.[91] It began erupting at least 250,000 years ago. In recorded history, major eruptions have been about 50 years apart,[91] in 1895, 1945, and 1995–1996. Minor eruptions are frequent, with at least 60 since 1945. Some of the minor eruptions in the 1970s generated small ash falls and lahars that damaged ski fields.[92] Between major eruptions, a warm acidic crater lake forms, fed by melting snow. Major eruptions may completely expel the lake water. Where a major eruption has deposited a tephra dam across the lake’s outlet, the dam may collapse after the lake has refilled and risen above the level of its normal outlet, the outrush of water causing a large lahar. The most notable lahar caused the Tangiwai disaster on December 24, 1953, when 151 people aboard a Wellington to Auckland express train were killed after the lahar destroyed the Tangiwai rail bridge just moments before the train was due. In 2000, the ERLAWS system was installed on the mountain to detect such a collapse and alert the relevant authorities.

The Auckland volcanic field on the North Island of New Zealand has produced a diverse array of explosive craters, scoria cones, and lava flows. Currently dormant, the field is likely to erupt again within the next “hundreds to thousands of years”, a very short timeframe in geologic terms.[93] The field contains at least 40 volcanoes, most recently active about 600 years ago at Rangitoto Island, erupting 2.3 km3 (0.55 cu mi) of lava.

Soil

The soils of the Pacific Ring of Fire include andosols, also known as andisols; they have formed by the weathering of volcanic ash. Andosols contain large proportions of volcanic glass.[94] The Ring of Fire is the world’s main location for this soil type, which typically has good levels of fertility.[95]

The Decade Volcanoes are 16 volcanoes identified by the International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth’s Interior (IAVCEI) as being worthy of particular study in light of their history of large, destructive eruptions and proximity to densely populated areas. The Decade Volcanoes project encourages studies and public-awareness activities at these volcanoes, with the aim of achieving a better understanding of the volcanoes and the dangers they present, and thus being able to reduce the severity of natural disasters.

They are named Decade Volcanoes because the project was initiated in the 1990s as part of the United Nations–sponsored International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction.

A volcano may be designated a Decade Volcano if it exhibits more than one volcanic hazard (people living near the Decade Volcanoes may experience tephra fall, pyroclastic flows, lava flows, lahars, volcanic edifice instability and lava dome collapse); shows recent geological activity; is located in a densely populated area (eruptions at any of the Decade Volcanoes may threaten tens or hundreds of thousands of people, and therefore mitigating eruption hazards at these volcanoes is crucial); is politically and physically accessible for study; and there is local support for the work.

Aims of the program

The general approach of Decade Volcano projects has been to convene a planning workshop, identify the major strengths and weaknesses of risk mitigation at each volcano, and to plan how to address the weaknesses identified. One of the difficulties faced in mitigating hazards at volcanoes is ensuring that geoscientists and those who will enact the mitigation measures communicate adequately with each other, and the Decade Volcano program has attempted to ensure this by making sure both groups are well represented at Decade Volcano workshops.[1]

Funding

Hopes that United Nations funding might be available for Decade Volcano projects did not come to fruition, and funding was sought instead from a variety of sources. For example, Mexican scientific and civil defence bodies funded work at Colima, principally for Mexican scientists but also for a few foreign colleagues; major bilateral French-Indonesian and German-Indonesian programs were initiated at Merapi; and the European Union has provided funding for many of the studies carried out at European volcanoes.

One particular activity that has not been funded—because it typically is not allowable under most national or bilateral funding—is the exchange of scientists and civil defence leaders between the various Decade Volcano projects of developing countries, for example, between the Philippines and Indonesia, or between Mexico, Guatemala, and Colombia, or across the Pacific and Atlantic. Often, scientists and civil defence leaders from developing countries can relate better to each other’s experiences than they can to the experience of counterparts from industrialized countries. Also, civil defence leaders who have experienced volcanic crises are far more credible witnesses, in the eyes of local civil defence leaders, than either local or visiting scientists might be.[1]

Achievements

Since it was initiated, the Decade Volcano program has achieved a number of successes in predicting volcanic events and mitigating disasters. One of the most notable was the successful diversion of a lava flow and blanket at Mount Etna in 1992. The flow was threatening the town of Zafferana, and had overwhelmed several barriers placed perpendicular to its flow down a valley. Scientists and civil defence leaders decided to try to dam the flow higher up, and did so by dropping large concrete blocks into a skylight in a lava tube which was feeding the flow. The flow subsequently stopped short of Zafferana.[2]

The program has significantly increased what is known about the Decade Volcanoes, some of which were very poorly studied before being designated. The eruptive history of Galeras volcano is now much better established than previously, and at Taal Volcano the importance of water in driving its explosive eruptions has come to light.

Measures which have been taken to mitigate disasters which might be caused by future eruptions include a new law in the vicinity of Mount Rainier, requiring assessment of geological hazards before any new developments; limitations on high density housing developments in the Taal Caldera; and the development of an evacuation plan for parts of Naples which might be affected in the event of an eruption at Vesuvius.[1]

Problems

Although studies at many Decade Volcanoes have clearly reduced the risks faced by nearby settlements, eruptions at some of the Decade Volcanoes have demonstrated the difficulties faced by the program. Eruptions at Japan’s Mount Unzen which began shortly before it was designated a Decade Volcano were heavily monitored, but despite this, a large pyroclastic flow killed 43 people, including three volcanologists.[3]

Later, a 1993 Decade Volcano conference in the city of Pasto, Colombia ended in disaster when several attending scientists mounted an impromptu expedition to the crater of Galeras. An unexpected eruption while they were at the summit killed six scientists and three tourists.[4]

Civil unrest in the vicinity of several of the Decade Volcanoes has also interfered with the program. The civil war in Guatemala affected studies of Volcán Santa María until a ceasefire was called in 1996, while ongoing civil war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has hampered studies of Nyiragongo volcano. More generally, scarce resources for volcano studies have led to programs competing for limited funding.[1]

Volcanoes selected

The following volcanoes were selected as the 16 current Decade Volcanoes:[5]

| Volcano | Elevation | Region | Country | Population at risk of lava/lahar /ash flow |

Last known eruption | Affected Region/Why a Decade Volcano |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avachinsky–Koryaksky | 2,741 m (8,993 ft) (Avachinsky) 3,456 m (11,339 ft) (Koryaksky) |

Kamchatka | Russia | 179,367 (2021 est)[6] |

2001 (Avachinsky),[7]2009 (Koryaksky)[8] | Proximity of volcano to Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky.[9] |

| Volcán de Colima | 3,820 m (12,533 ft) | Colima/ Jalisco | Mexico | 770,000 (2019 est)[10] |

2019[11] | Whole of Colima State |

| Galeras | 4,276 m (14,029 ft) | Nariño | Colombia | 1,630,000 (2018 est)[12] |

2014[13] | Whole of Nariño Department |

| Mauna Loa | 4,169 m (13,678 ft) | Hawaii | United States | ? | 2022[14] | Largest of the active shield volcanoes in the Hawaiian Islands. Lower flanks populated in multiple directions, but most dangerous to the city of Hilo |

| Mount Etna | 3,326 m (10,912 ft) | Sicily | Italy | 1,100,000[15] | 2013–present | Whole metro city of Catania in general due to air pollution and ash clouds. Capable of lava bombs and violent VEI 3 eruptions. |

| Mount Merapi | 2,910 m (9,547 ft) | Central Java/ Special Region of Yogyakarta | Indonesia | 5,050,000 (2019 est)[16] |

2024 | Whole of Special Region of Yogyakarta, and Klaten Regency |

| Mount Nyiragongo | 3,470 m (11,385 ft) | North Kivu | Democratic Republic of the Congo | 2,000,000 | 22 May 2021 – present, VEI 0-2. | No census for decades in sprawling city of Goma. Lava known to be highly fluid and fast-moving. May 2021 eruption killed 32 people and injured thousands.[17] Currently not monitored for seismic activity. |

| Mount Rainier | 4,392 m (14,409 ft) | Washington | United States | 795,000 (2010) |

1894-1895, (minor phreatic) | Whole of Pierce County, and potentially as far as Seattle. Mount Rainier is one of the most glaciated stratovolcanoes in the Cascade Volcanic Arc. Capable of setting off massive lahars, as evidenced in the valleys below it in all directions. Known to have had both landslide type lahars or snowmelt lahars. Considered by USGS to be one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the USA.[18] |

| Mount Vesuvius | 1,281 m (4,203 ft) | Campania | Italy | 3,085,000[15] | 17-23 March 1944, VEI 3 | Whole metro city of Naples. Very long record of destroying cities nearby, capable of large pyroclastic flows. Destroyed Herculaneum and Pompeii in 79 AD, VEI 5 eruption. |

| Mount Unzen | 1,486 m (4,875 ft) | Nagasaki/ Kumamoto | Japan | 1,320,000 (2019 est)[19] |

1995 | Nagasaki Prefecture, tsunami potential |

| Sakurajima | 1,117 m (3,665 ft) | Kagoshima | Japan | 1,470,000 (2019 est)[19] |

2022[20] | Whole of Kagoshima Prefecture except Amami Islands |

| Santa María | 3,772 m (12,375 ft) | Quetzaltenango | Guatemala | 1,127,000 (2018 est)[21] |

23 August 2013 | Whole of Quetzaltenango and Retalhuleu Departments |

| Santorini (Thera) | 367 m (1,204 ft) | South Aegean | Greece | ? | 1950 | Entire island of Santorini once much larger. In 1646 BCE, Santorini, then called Thera, had an eruption more powerful than the 1880s eruption at Krakatoa.[22] Currently what was one island is now three with caldera hidden below surface. Risk of tsunami; record of causing one in 1646 BCE.[23] |

| Taal Volcano | 311 m (1,020 ft) | Calabarzon | Philippines | 24,393,000 (2020 est)[24] |

2021 | Whole areas of Batangas, Cavite, Metro Manila and Laguna |

| Teide | 3,715 m (12,188 ft) | Canary Islands | Spain | 900,000 | 1909 | Tenerife, tsunami potential |

| Ulawun | 2,334 m (7,657 ft) | East New Britain / West New Britain | Papua New Guinea | ? | November 2023[25] | ? |